Is Vitamin D Supplementation Alone Sufficient for the Health Benefits of Vitamin D? The Importance of VDR (Vitamin D Reduction)

People often think that taking only vitamin D3 supplements is enough to reap the benefits associated with vitamin D. However, vitamin D3 alone is often insufficient. The vitamin D receptor (VDR) also has numerous other extremely important functions.

Conditions Required for Obtaining Active Vitamin D and Subsequent Procurement

We tend to think of vitamin D3 as the cause of many health effects; however, in reality, vitamin D3 is only the beginning of the process leading to these benefits.

When UVB rays from sunlight touch our bare skin under suitable conditions , a series of enzymatic reactions occur in different organs. An enzyme means a protein. A protein means the gene sequence that codes for it.

*Suitable Conditions: During the periods when the sun’s zenith angle is shortest in the geographical location (May-October for Turkey, midday hours), approximately 18-20 mJ of sunlight with a wavelength of 290-310 nm falling directly on bare, non-dark-colored human skin without sunscreen for about 10 minutes can produce 10,000-20,000 IU of Vitamin D.

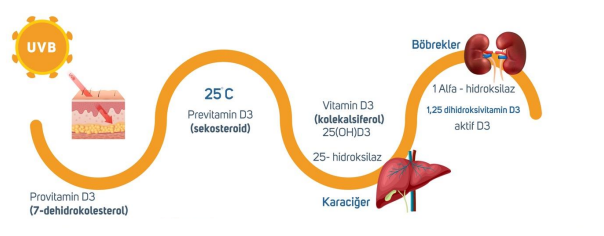

Provitamin D3 is converted to previtamin D3 after ultraviolet B (UVB) rays come into contact with the skin. Previtamin D3 is then converted to vitamin D3 (25-OH-D3/cholecalciferol) in the liver by the 25-hydroxylase enzyme encoded by the CYP2R1 gene.

Even if the pathways leading to vitamin D3 production are successfully completed, this is not sufficient; vitamin D3 must also be converted into its active form, calcitriol. This process takes place in the kidneys, where cholecalciferol is converted to the active form calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) by the 1-alpha hydroxylase enzyme encoded by the CYP27B1 gene. (Excess calcitriol is inactivated by 24-hydroxylase encoded by CYP24A1.) Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Calcitriol then needs to be transported by carrier proteins (GCs) to successfully bind to the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR). This requires a healthy carrier protein genetic code and receptor structure.

Aside from genetic problems such as the fairly common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), some infections and toxins are also known to block these receptors. In such cases, neither calcitriol nor vitamin D3 exhibit any health benefits.

After calcitriol successfully binds to the VDR, a specific vitamin-receptor complex must be formed to maintain many physiological functions, such as normal cell proliferation and apoptosis. This complex is a key member of the nuclear receptor superfamily. For the complex to be completed, calcitriol bound to the VDR must bind to the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR), which is activated by active vitamin A, to form a dimer. The VDR-calcitriol-RXR complex, upon reaching the cell nucleus, can regulate genes containing the Vitamin D Response Element (VDRE) in its promoter region. Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Following all of this, cell-specific responses can occur, and the expression of specific genes encoding proteins that regulate the effects of vitamin D can be controlled. The gene expressions that occur here constitute 10% of the expressions that occur in the entire genetic code. Considering that VDRs are thought to be present in approximately 31 organs, this percentage reveals how important vitamin D3 and all the subsequent events are for survival and maintaining a healthy life.

Therefore, to experience the health benefits of vitamin D, the first requirement is sufficient vitamin D intake. Supplements are valuable at this stage. However, let’s not forget that obtaining active vitamin D requires a healthy genetic code, healthy enzymes, healthy transporters, a healthy receptor, and vitamin A-activated RXR. Therefore, vitamin A can also be supplemented if necessary. Since epigenetics has taught us that we can change our genetic code, trying to optimize our genetic codes through our lifestyle and dietary choices is also valuable.

will be.

Benefits of Vitamin D3

Calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, has numerous benefits. Vitamin D protects against:

-

Osteoporosis

-

Cancer

-

Diabetes (Type 1 and Type 2)

-

Heart diseases

-

Neurological diseases

-

Psoriasis

-

Infections

-

Multiple sclerosis

-

Asthma

-

Kidney inflammation and death due to kidney disease (creatinine levels are expected to decrease)

-

High blood pressure (suppresses the renin/angiotensin system)

-

Lupus / SLE

-

Arthritis

-

Scleroderma

-

Sarcoidosis

-

Sjögren’s syndrome

-

Autoimmune thyroid diseases (Hashimoto’s, Graves’)

-

Ankylosing spondylitis

-

Reiter syndrome

-

Uveitis

Vitamin D is particularly beneficial for individuals with a Th1 and Th17 dominant immune profile .

The Anti-Inflammatory Role of Vitamin D

Vitamin D primarily suppresses the adaptive immune system .

-

It inhibits B cell proliferation.

-

It reduces immunoglobulin (Ig) secretion.

-

It inhibits T cell proliferation.

-

It allows you to shift from Th1 to Th2.

-

It suppresses Th17

-

It increases the number of Tregs and IL-10s.

-

It reduces inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNF-α, IL-17, IL-21)

-

It lowers TGF-beta.

-

It inhibits dendritic cell differentiation and maturation by reducing the expression of MHC II and co-stimulatory molecules.

Strengthens the Immune System

Vitamin D also stimulates the natural (innate) immune system :

-

It is critical for T cell activation; in this respect, it has an immune-boosting effect.

-

It increases CD8+ T cells, which are important in controlling viral infections.

-

It increases natural killer T cells (NKT) – beneficial for autoimmune diseases, but may be detrimental for asthma.

-

It increases NK cells.

-

It increases the release of antimicrobial agents such as cathelicidin and beta-defensin-4 in response to infection.

Other Benefits of Vitamin D Receptors

The best-known benefit of vitamin D3 is bone health .

-

Low blood D3 levels are associated with low bone density.

-

Clinical studies have shown that calcitriol is beneficial for people with low bone density.

VDR activation increases the expression of liver and intestinal Phase I detoxification enzymes (e.g., CYP2C9, CYP3A4) that play a crucial role in drug and toxin metabolism.

Vitamin D receptors are important for hair growth; in experimental animals, VDR loss is associated with hair loss.

VDR regulates the transport of calcium, iron, and other minerals from the intestines.

Since many infections block the VDR (Ventricular Defect), the body cannot effectively fight these pathogens. Researchers have successfully used combinations of calcitriol and antibiotics in many cases. To reduce immune responses, it is recommended to gradually eliminate pathogens over years.

Calcitriol/VDR increases dopamine levels by increasing tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine production.

This effect is observed in the hypothalamus, adrenal glands, substantia nigra, and possibly other brain regions. This results in increased production of dopamine, adrenaline, and noradrenaline. However, tyrosine hydroxylase can also increase oxidative stress.

Calcitriol increases GABA levels by increasing GAD67. Calcitriol also increases GDNF, which protects dopamine neurons (in vitro).

Researchers suggest that circulating vitamin D deficiency may lead to substantia nigra dysfunction, where dopaminergic degeneration is seen in Parkinson’s disease.

Vitamin D deficiency is common in Parkinson’s patients, and the disease is associated with low bone mineral density.

The effects of active D on cancer vary depending on the tissue.

-

In breast cancer, estrogen and aromatase decrease, while testosterone/androgens increase (positive).

-

DHT decreases in adrenal cancer (positive)

-

In prostate cancer, testosterone and DHT increase (negative).

In lung and breast cancer, elevated levels of the enzyme that breaks down active D have been observed; this suggests that increasing active D levels may be beneficial.

Active vitamin D increases prolactin production.

Technique: 1.25D; regulates RANKL, SPP1 and osteocalcin for bone mineral remodeling; TRPV6, CaBP(9k) and claudin-2 for intestinal calcium absorption; and TRPV5, klotho and Npt2c for renal calcium and phosphate reabsorption.

Natural Ways to Increase Calcitriol and Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) Gene Expression

-

Exercise increases calcitriol levels.

-

RXR (and retinol) are required to produce proteins with VDR. 1,25-D3 binds to VDR; it then associates with RXR to activate gene expression. (Not all VDR-dependent genes require RXR.)

-

Lactobacillus rhamnossus GG and L. reuteri probiotic supplementation .

-

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) – increases calcitriol/1,25 D3 and increases PTH-related peptide,

-

SIRT1 – potentiates VDR – Acetylation of VDR reduces 1.25D/VDR signaling. SIRT1 enhanced the ability of VDR to associate/bind with RXR.

-

PGC-1a potentiates the VDR. It is a co-activator of the VDR, but still requires 1.25D3.

-

Dopamine

-

Bile – specifically lithocolic acid or LCA. VDR evolved from a structure whose ancient role was as a detoxification nuclear receptor. LCA is produced by gut bacteria (through the metabolism of liver-derived chenodeoxycholic acid). LCA travels to the colon; there, VDR binds to LCA, or 1,25D, and activates the CYP3A4 and SULT2A genes, which facilitate its removal from the cell via the ABC efflux transporter.

-

Omega-3: DHA, EPA – Fish oil/DHA

-

Omega-6 : γ-Linolenic acid, Arachidonic acid

-

Curcumin – Curcumin is more active than LCA/bile in dragging VDR-mediated transcription and binds to VDR with approximately the same affinity as LCA.

-

Resveratrol potentiates VDR in the following ways: (1) by potentiating the binding of 1,25D to VDR; (2) by activating RXR; (3) by stimulating SIRT1.

-

Forskolin increases 25D3 to 1.25D3 in vitro.

-

Gamma Tocotrienol – Tocotrienols or Tocopherols (IHERB)

-

Vitamin E/alpha-tocopherol does not compete with calcitriol for VDR.

-

Dexamethasone – does not compete with 1.25.

-

Interferon-gamma – IFN-γ treatment inhibited the induction of 24-hydroxylase (the enzyme that breaks down 1,25D3) of 1,25D3. This means that 1,25D3 was increased. (Technical: IFNγ did not alter the basal level activity of the promoter and the binding of 1,25D to the VDR.)

or did not alter nuclear VDR levels. (IFN-γ disrupts the binding of VDR-RXR to VDRE via a Stat1-mediated mechanism)

-

Estradiol increases VDR expression and calcitriol levels.

-

Phytoestrogens

-

Testosterone

-

Prostaglandins

-

Bisphosphonates

DHA, EPA, linoleic acid, and arachidonic acid all together activate VDR compared to 1.25 D3.

It is 10,000 times less effective.

Curcumin is 1,000 times less effective at inducing VDR gene expression compared to 1,25 D3. Curcumin and bile have similar binding ability to VDR and similar gene expression levels.

Curcumin, bile, DHA, EPA, and arachidonic acid all compete with 1,25D3 for binding. Dexamethasone and alpha-tocopherol do not compete.

Naturally, the question arises: if these are competitive connectors and have a much lower connection capacity to the VDR, would they still work? The answer seems to be yes.

High concentrations of PUFAs can form in selected cells or tissues and exhibit biological activity.

Excessive bile/LCA administered to mice produced the same effect as that produced by 1,25D3 (specifically, calcium transport activation).

Renal gland tissue may contain approximately 1.25% vitamin D.

Factors that Suppress VDR or Calcitriol

-

Caffeine

-

Cortisol / glucocorticoids

-

Prolactin

-

Thyroid hormones

-

TGF-beta

-

TNF

-

Corticosteroids

-

Phosphatonin, ketoconazole, heparin, thiazides

-

Ubiquitin

Pathogens that Inhibit the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR)

Many pathogens inhibit some aspect of the vitamin D system — either the VDR (Vitamin D Receptor), the ability of molecules to bind to the VDR, or the VDR’s capacity to generate gene expression. These are just a few examples; however, I don’t think I’ve covered everything currently known in the scientific community.

-

-

P. aeruginosa (most often hospital-acquired). It produces the sulfonolipid ligand capnine. Antibiotics are not effective against it.

-

H. pylori (responsible for stomach ulcers). Found in 50% of the world’s population. Produces the sulfonolipid ligand capnine.

-

Lyme/Borrelia – Live Borrelia (in monocytes) reduce VDR by 50-fold, and “dead” Borrelia reduce it by 8-fold – This may explain why people develop autoimmune conditions after Lyme infection.

-

Tuberculosis – Reduces VDR by 3.3 times.

-

Capnin is formed by “gliding” biofilm bacteria.

-

It has been shown – Capnine (Cytophaga, Capnocytophaga, Sporocytophaga and Flexibacter)

-

-

Chlamydia (trachomatis)

-

Shigella – an algae found in stool that causes intestinal problems and diarrhea.

-

Bacteria increase caspase-3, a protein that breaks down VDR structure and thus limits the VDR’s ability to transcribe genes.

-

-

Mycobacterium leprase produces mir-21 to target multiple genes associated with VDR.

-

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) – reduces VDR by approximately five times. EBV also blocks the ability of VDR to produce its products.

-

HIV – It binds to VDR and inhibits its conversion to active D.

-

Aspergillus fumigatus – In cystic fibrosis patients, the fungus A. fumigatus has been shown to secrete gliotoxin; this toxin reduces VDR in a dose-dependent manner.

-

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reduces VDR by 2.2 times.

-

Hepatitis C virus – It inhibits CYP24A1, the enzyme responsible for breaking down excess 1,25-D.

-

When bacterial products block VDR, less CYP24A1 is produced, leading to an excess of active vitamin D, as seen in many autoimmune conditions.

High Calcitriol Levels Indicate Inflammatory/Autoimmune Disease

As bacterial products disrupt VDR activity, the receptor is inhibited from expressing an enzyme (CYP24) that breaks down calcitriol/1,25-D into its inactive metabolites. This allows 1,25-D levels to rise without a feedback system to keep them in balance, leading to high levels of the hormone.

Studies show a strong association between these autoimmune conditions and 1,25-D levels above 110 pmol/L (46 pg/mL), even in the absence of cases of significantly high blood calcium levels. In a group of 100 people with autoimmune conditions, 38 had values above 160 pmol/L (66.6 pg/mL).

In individuals with chronic inflammation, active vitamin D levels are often found to be between 50–80 pg/mL.

In contrast, there is little association with vitamin D deficiency or other inflammatory markers; therefore, it can be assumed that blood levels of vitamin D3 or 1,25-D are a sensitive measure for assessing autoimmune disease status.

Acquired hormone resistance is also known as resistance to insulin, thyroid hormones, steroid hormones, and growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), and high levels of these hormones are seen in some autoimmune conditions.

Understanding Calcitriol Levels with Vitamin D3

Common blood tests measure various markers that indicate how much active vitamin D you have.

The following indicate higher calcitriol levels:

-

-

Higher parathyroid hormone levels

-

Higher blood calcium and phosphorus levels.

-

Higher albumin

-

Higher creatinine

-

Lower alkaline phosphatase

-

Since at least some (perhaps all) of these require the vitamin D receptor, checking blood levels of Calcitriol Active/Vitamin D (1,25 Hydroxy) along with other tests can indicate the degree of VDR resistance.

SOURCE

- Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action. Calcified tissue international, 92(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-012-9619-0

- Haussler, M.R., Whitfield, G.K., Kaneko, I., Haussler, C.A., Hsieh, D., Hsieh, J.C., & Jurutka, P.W. (2013).

- Lips, P., & van Schoor, N. M. (2011). The effect of vitamin D on bone and osteoporosis. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism, 25(4), 585–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2011.05.002

- Garland, C.F., Garland, F.C., Gorham, E.D., Lipkin, M., Newmark, H., Mohr, S.B., & Holick, M.F. (2006). The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. American journal of public health, 96(2), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.045260

- Schwalfenberg G. (2008). Vitamin D and diabetes: improvement of glycemic control with vitamin D3 repletion. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 54(6), 864–866.

- Waterhouse, J. C., Perez, T. H., & Albert, P. J. (2009). Reversing bacteria-induced vitamin D receptor dysfunction is key to autoimmune disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1173, 757–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749- 6632.2009.04637.x

- Bassuk, SS, & Manson, J. E. (2009). Does vitamin D protect against cardiovascular disease? Journal of cardiovascular translational research, 2(3), 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-009-9111-z

- Annweiler, C., Schott, A.M., Berrut, G., Chauviré, V., Le Gall, D., Inzitari, M., & Beauchet, O. (2010). Vitamin D and aging: neurological issues. Neuropsychobiology, 62(3), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1159/000318570

- Barrea, L., Savanelli, M.C., Di Somma, C., Napolitano, M., Megna, M., Colao, A., & Savastano, S. (2017). Vitamin D and its role in psoriasis: An overview of the dermatologist and nutritionist. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders, 18(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-017-9411-6

- Yamshchikov, AV, Desai, NS, Blumberg, HM, Ziegler, TR, & Tangpricha, V. (2009). Vitamin D for treatment and prevention of infectious diseases: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Endocrine practice: official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, 15(5), 438–449. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP09101.ORR

- Salzer, J., Hallmans, G., Nyström, M., Stenlund, H., Wadell, G., & Sundström, P. (2012). Vitamin D as a protective factor in multiple sclerosis. Neurology, 79(21), 2140–2145. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182752ea8

- Shen, SY, Xiao, WQ, Lu, JH, Yuan, MY, He, JR, Xia, HM, Qiu, X., Cheng,

- KK, & Lam, KBH (2018). Early life vitamin D status and asthma and wheeze: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC pulmonary medicine, 18(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0679-4

- Paul, G., Brehm, J. M., Alcorn, J. F., Holguín, F., Aujla, S. J., & Celedón, J. C. (2012).

- Vitamin D and asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 185(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201108-1502CI

- Arfian, N., Muflikhah, K., Soeyono, S.K., Sari, D.C., Tranggono, U., Anggorowati, N., & Romi, M.M. (2016). Vitamin D Attenuates Kidney Fibrosis via Reducing Fibroblast Expansion, Inflammation, and Epithelial Cell Apoptosis. The Kobe journal of medical sciences, 62(2), E38–E44.

- Tamez, H., Kalim, S., & Thadhani, R. I. (2013). Does vitamin D modulate blood pressure? Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension, 22(2), 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835d919b

- Aranow C. (2011). Vitamin D and the immune system. Journal of investigative medicine: the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research, 59(6), 881–886. https://doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0b013e31821b8755

- Ardizzone, S., Cassinotti, A., Trabattoni, D., Manzionna, G., Rainone, V., Bevilacqua, M., Massari, A., Manes, G., Maconi, G., Clerici, M., & Bianchi Porro, G. (2009). Immunomodulatory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on TH1/TH2 cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: an in vitro study. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology, 22(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/039463200902200108

- Irani, M., Seifer, D.B., Grazi, RV, Julka, N., Bhatt, D., Kalgi, B., Irani, S., Tal, O., Lambert-Messerlian, G., & Tal, R. (2015). Vitamin D Supplementation Decreases TGF-β1 Bioavailability in PCOS: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 100(11), 4307–4314. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-2580

- Cantorna, M. T., Zhao, J., & Yang, L. (2012). Vitamin D, invariant natural killer T-cells and experimental autoimmune disease. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 71(1), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665111003193

- Mariani, E., Ravaglia, G., Meneghetti, A., Tarozzi, A., Forti, P., Maioli, F., Boschi, F., & Facchini, A. (1998). Natural immunity and bone and muscle remodeling hormones in the elderly. Mechanisms of aging and development, 102(2-3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0047-6374(97)00173-5

- Cranney, A., Horsley, T., O’Donnell, S., Weiler, H., Puil, L., Ooi, D., Atkinson, S., Ward, L., Moher, D., Hanley, D., Fang, M., Yazdi, F., Garritty, C., Sampson, M., Barrowman, N., Tsertsvadze, A., & Mamaladze, V. (2007). Effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone health. Evidence report/technology assessment, (158), 1–235.

- Peppone, L. J., Hebl, S., Purnell, J. Q., Reid, ME, Rosier, RN, Mustian, K. M., Palesh, OG, Huston, A. J., Ling, M. N., & Morrow, GR (2010). The efficacy of calcitriol therapy in the management of bone loss and fractures: a qualitative review. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis

- Foundation of the USA, 21(7), 1133–1149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1136-2

- Reschly, E. J., & Krasowski, M. D. (2006). Evolution and function of the NR1I nuclear hormone receptor subfamily (VDR, PXR, and CAR) with respect to metabolism of xenobiotics and endogenous compounds. Current drug metabolism, 7(4), 349–365. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920006776873526

- Luderer, H.F., & Demay, M.B. (2010). The vitamin D receptor, the skin and stem cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, 121(1-2), 314–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.01.015

- Fleet, J. C., & Schoch, R. D. (2010). Molecular mechanisms for regulation of intestinal calcium absorption by vitamin D and other factors. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences, 47(4), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408363.2010.536429

- Cui, X., Pertile, R., Liu, P., & Eyles, D. W. (2015). Vitamin D regulates tyrosine hydroxylase expression: N-cadherin a possible mediator. Neuroscience, 304, 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.07.048

- Jiang, P., Zhang, LH, Cai, HL, Li, HD, Liu, YP, Tang, MM, Dang, RL, Zhu,

- W. Y., Xue, Y., & He, X. (2014). Neurochemical effects of chronic administration of calcitriol in rats. Nutrients, 6(12), 6048–6059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6126048

- Puchacz, E., Stumpf, W. E., Stachowiak, E. K., & Stachowiak, M. K. (1996). Vitamin D increases expression of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene in adrenal medullary

- cells. Brain research. Molecular brain research, 36(1), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-328x(95)00314-i

- Gatto, NM, Sinsheimer, JS, Cockburn, M., Escobedo, LA, Bordelon, Y., & Ritz,

- B. (2015). Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and Parkinson’s disease in a population with high ultraviolet radiation exposure. Journal of the neurological sciences, 352(1-2), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.03.043

- Lundqvist, J., Norlin, M., & Wikvall, K. (2011). 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 exerts tissue-specific effects on estrogen and androgen metabolism. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1811(4), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.01.004

- Chen, G., Kim, SH, King, AN, Zhao, L., Simpson, RU, Christensen, PJ, Wang,

- Z., Thomas, D.G., Giordano, T.J., Lin, L., Brenner, D.E., Beer, D.G., & Ramnath, N. (2011). CYP24A1 is an independent prognostic marker of survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 17(4), 817–826. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078- 0432.CCR-10-1789

- Lopes, N., Sousa, B., Martins, D., Gomes, M., Vieira, D., Veronese, L.A., Milanezi, F., Paredes, J., Costa, J.L., & Schmitt, F. (2010). Alterations in Vitamin D signaling and metabolic pathways in breast cancer progression: a study of VDR, CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 expression in benign and malignant breast lesions. BMC cancer, 10, 483. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-483

- Castillo, A.I., Jimenez-Lara, A.M., Tolon, R.M., & Aranda, A. (1999). Synergistic activation of the prolactin promoter by vitamin D receptor and GHF-1: role of the coactivators, CREB-binding protein and steroid hormone receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1). Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.), 13(7), 1141–1154. https://doi.org/10.1210/mend.13.7.0320

- Zittermann, A., Sabatschus, O., Jantzen, S., Platen, P., Danz, A., Dimitriou, T., Scheld, K., Klein, K., & Stehle, P. (2000). Exercise-trained young men have higher calcium absorption rates and plasma calcitriol levels compared with age-matched sedentary controls. Calcified tissue international, 67(3), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002230001132

- Zittermann, A., Sabatschus, O., Jantzen, S., Platen, P., Danz, A., & Stehle, P. (2002). Evidence for an acute rise of intestinal calcium absorption in response to aerobic exercise. European journal of nutrition, 41(5), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-002-0375-1

- Armbrecht, H. J., Forte, L. R., Wongsurawat, N., Zenser, T. V., & Davis, B. B. (1984).

- Forskolin increases 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production by rat renal slices in vitro. Endocrinology, 114(2), 644–649. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-114-2-644

- Dampf Stone, A., Batie, SF, Sabir, MS, Jacobs, ET, Lee, JH, Whitfield, GK, Haussler, MR, & Jurutka, PW (2015). Resveratrol potentiates vitamin D and nuclear receptor signaling. Journal of cellular biochemistry, 116(6), 1130–1143. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.25070

- Savkur, R.S., Bramlett, K.S., Stayrook, KR, Nagpal, S., & Burris, T.P. (2005). Coactivation of the human vitamin D receptor by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha. Molecular pharmacology, 68(2), 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.105.012708

- Matkovits, T., & Christakos, S. (1995). Ligand occupancy is not required for vitamin D receptor and retinoid receptor-mediated transcriptional activation. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.), 9(2), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1210/mend.9.2.7776973

- Han, S., Li, T., Ellis, E., Strom, S., & Chiang, J. Y. (2010). A novel even acid-activated vitamin D receptor signaling in human hepatocytes. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.), 24(6), 1151–1164. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2009-0482

- Haussler, M.R., Haussler, C.A., Bartik, L., Whitfield, G.K., Hsieh, J.C., Slater, S., & Jurutka, P.W. (2008). Vitamin D receptor: molecular signaling and actions of nutritional ligands in disease prevention. Nutrition reviews, 66(10 Suppl 2), S98– S112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00093.x

- Vidal, M., Ramana, C.V., & Dusso, A.S. (2002). Stat1-vitamin D receptor interactions antagonize 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D transcriptional activity and enhance stat1-mediated transcription. Molecular and cellular biology, 22(8), 2777–2787. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.22.8.2777-2787.2002

- Liel, Y., Shany, S., Smirnoff, P., & Schwartz, B. (1999). Estrogen increases 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D receptors expression and bioresponse in the rat duodenal mucosa. Endocrinology, 140(1), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.140.1.6408

- Gilad, L.A., Bresler, T., Gnainsky, J., Smirnoff, P., & Schwartz, B. (2005). Regulation of vitamin D receptor expression via estrogen-induced activation of the ERK 1/2 signaling pathway in colon and breast cancer cells. The Journal of endocrinology, 185(3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.1.05770

Leave A Comment